The Girl With No Place to Hide gave me everything I wanted from a 1950s private eye novel—and in spades. A thoroughly hardboiled protagonist, gritty New York city ambience, wild nights in Greenwich Village bars, Bronx flophouses, incriminating photographs, two-way mirrors, blackmail, loan-sharks, shoot-outs, fist-fights, jail-house brawls, prizefights at Madison Square Garden, thugs, crooked cops, duplicitous dames—you name it, this book’s got it. But it’s also got something extra special—and that’s Marvin Albert.

The story begins when a young woman enters a bar looking for private eye Jake Barrow’s friend, fight manager Steve Canby, who left the bar just moments before. Later, as Jake is leaving the bar, he finds a thug in the alley strangling the woman. He rescues her and takes her to his apartment for safe keeping, and she reveals that she’s in trouble, and that something bad has happened to her friend Ernie. Before Jake can find out more, he gets an urgent call to come up to the Bronx for $200. When he gets there, he realizes it was a ruse. Returning to his apartment, Angela is gone. The next morning, Jake sees in the newspaper that a photographer named Ernie was found murdered—and he fears that Angela will be the next victim.

I’ll say no more except that this is a wild ride all across New York City, with plenty of twists and turns that kept me guessing every step of the way.

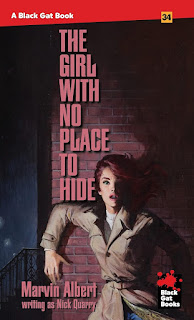

Originally appearing under Albert's pseudonym “Nick Quarry” in 1959 by Gold Medal Books, The Girl With No Place to Hide was recently reissued by Black Gat Books from Stark House Press, and it magnificently captures why Albert was a writer’s writer. The Girl With No Place to Hide is the work of a real pro—a slickly designed plot that hits the right beats but not in the expected places, so readers will get what they're looking for but not in the same way they’ve read it before. Albert also shows restraint with the prose, no leaning too much on sex, violence, or slang. This is Albert’s third novel with his series character Jake Barrow—but don’t let that stop you from jumping in. If you’re like me and you haven’t read the first two yet, you’ll have no trouble following along (though you might want to rush out and find the others).